Anthroposophic psychology: What is it?

Six Perspectives

- Our Mission Statement and what do these terms mean? "Anthroposophic psychology" defined.

- The Counselor... As If Soul and Spirit Matter — an introduction for anyone.

- ANTHROPOSOPHIC PSYCHOLOGY: Caring for the Human Soul by Roberta Nelson, Ph.D.

- Introducing Anthroposophic Psychology in Relation to Mainstream Psychology, by David Tresemer, Ph.D.

- What is AAP? by Christine Huston, AAP Associate

- About AAP by Dr. James Dyson, AAP Faculty Member

VIDEO UPDATE for 2024:

|

1. mission statement and what do these terms mean? |

The Mission Statement of AAP Psychology is: "Re-membering Psychology through Relational Anthropos-Sophia."

Rudolf Steiner often declined to define; he preferred to characterize. This is appropriate to energies, bodies, and forces whose nature is to change and transform. Here are some characterizations:

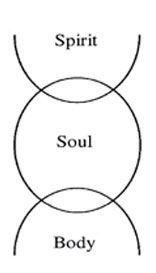

- Psyche—Greek for "soul." Soul is the workshop, employing the capacities of thinking, feeling, and willing (head, heart, and hand), wherein the individuality (the "I") meets the challenges of a life. We awaken in our soul realm. Were we only physical, we would not have the sense "I am awake and present." Soul mediates between (and interpenetrates to a degree) body and spirit. Knowing these realms is essential to understanding the human being.

- Logos—Greek for pattern or creative-Word or rhythm, as well as for clear thinking (logic), thus order. We make sense of the dynamics of the world and of the flurry of thoughts and feeling in our soul life (psyche) by ordering our experiences, through psych-ology.

- Anthropos—the concept and then the experience that there exists a being whose name is Humanity. We each contribute a small bit to this great being through the development that we achieve in our individual lives-through the maturing that we do in response to the ups and downs that occur for everyone. Anthropos (a Greek word, also used in "anthropology") has a long-view task of immense proportions.

- Sophia—often translated "wisdom," a feminine/receptive principle of immense scope, including the creative force of our planet, the source of the mystery of animating life (still a mystery to science despite limited success in imitating life). Sophia is the unique body of our earth, in her various elements (earth, water, air, warmth). Though some scientists demean the being of Sophia, promising other planets just as lush and beautiful to which we can fly (and finding none), other scientists recognize the awesome opportunity that human souls have been given. True awe leads to a gratitude and reverence for what we have been given.

To engage these forces, RELATIONSHIP IS ESSENTIAL . When we see another human being stray from his or her path of development-into realms of dysfunction, suffering, and mental illness—it calls forth the "counselor" in us (from root words meaning to talk together). In anthroposophic psychology, talk is neither cheap nor worthless; indeed, words are precious and, when empowered by love, healing for both speaker and listener.

2. The Counselor... As If Soul and Spirit Matter

(Excerpt from chapter 1 of The Counselor … As if Soul and Spirit Matter)

A counselor can be found in many places. A counselor sits with a client who is trying to decide whether or not to take a job offer. A counselor facilitates a group meeting of trauma survivors. A "life coach," a kind of counselor, helps a client make priorities in his or her life. A psychotherapist listens to a client describe dreams of glory from the night before, and guides the client to distinguish the personal associations from the timeless myths activated in the dream. A lawyer, often called a counselor, discusses a pre-nuptial agreement with a client. A medical doctor ponders different choices for surgery with a patient. Friends walk together poring over the feelings of one of them struggling through a painful divorce. Lawyers, policemen, funeral directors, school teachers, eco-tourism guides, human resources departments in every company, the military (when in the "winning hearts and minds" mode), financial planners, social workers, nurses and doctors, wedding planners: All of these involve counseling, some professional, some personal.

An uncle can give warm and wise counsel to a niece or nephew. A "licensed professional clinical counselor" (LPCC) can wear a white lab coat and move through a hospital-like institution for treatment of drug addicts. A counselor can be everything in between. There are thousands of such counselors — some say fifty thousand "life coaches" in the United States alone, in addition to the more thoroughly trained licensed counseling psychologists. If you add in everyone who mentors another, or who listens, counseling includes everybody.

Each form of counseling involves the encounter between someone in need-the client, the friend — and someone who has more life experience, someone who can guide the one in need with recommendations, advice, plans for action ... or simply through listening. Counsel comes from the ancient Proto-Indo-European roots kom- (together) and kele- (call, speak), sharing these same roots with conciliate, council, and consult.

In any encounter between two human beings, especially where one is asking and the other is giving, there are assumptions — about who are you and who am I, about what it means to be a human being, about where life comes from and where it's going. Assumptions underlie the definition of a "problem," whether it's only a passing bad experience, or an indication of an inherently deficient person, or an opportunity with positive future value. There are assumptions about what is the appropriate exchange for me to engage in your "problem"— money, or you listening to me too, or some other exchange. Many factors determine the quality and outcomes of the encounter. Counselors vary widely in their philosophies and methods. Given the wide variety of human conundrums, there is room for many different forms of counseling.

A recent trend is to treat the human being as a bag of chemicals that can be adjusted by the right psychotropic drugs. In that view, all that matters is physical matter. The Counselor asks if soul and spirit matter; the play on the word "matter" is intentional. What matters? Is it only something that can be defined by number, weight, and measure? Or can you touch the substantiality of soul and spirit? Can you feel the truth of these phenomena?

In this book we introduce a way of understanding counseling and the counselor, based on the philosophy of "anthroposophy" — "Anthropos" — Greek for the possible and becoming human being — "Sophia" — the feminine principle of creation from divine thought into living matter. Though I will examine these terms in greater depth below, we can notice a first impression of a cooperation between a cosmic act of creation and the destiny of humanity.

Originally developed by the Austrian philosopher Rudolf Steiner in the early 1900s, and elaborated by others since then, anthroposophy emphasizes the preciousness of each and every human being, because of the workings of soul and spirit. A word should be said about Rudolf Steiner, the historical and continuing source of the intimate understanding of Anthropos in relation to Sophia. Though others have brought his concepts into modern language and applications, there are many ideas and concepts that he shared — amazing conceptions often shared only once in his six thousand lectures, never to be revisited — that help us formulate an entirely new approach to psychology, to the human being, to counseling. He lived from 1861 to 1925. In addition to his many lectures, sometimes four a day on different topics, he wrote a dozen books. He inspired a wide range of initiatives, from Waldorf schools and their special curricula, to biodynamic farming, to anthroposophic medicine, to a comprehensive art of movement named eurythmy, and others. The Anthroposophical Society exists in many countries; the international headquarters are in Dornach, Switzerland.

Though we will reveal many of the principles of anthroposophic psychology in this chapter and in this book, anthroposophy cannot be grasped only with the intellect. An experienced counselor already knows the limits of thinking: The intellect is helpful, but inadequate to the tasks that face a counselor. We need other tools to receive the guidance that anthroposophic psychology has to offer.

(Later in that first chapter)

Anthroposophic psychology understands human existence in ways not found in mainstream psychology. I have found it useful to define anthroposophic psychology by a short list of points of uniqueness. These are spirit, spirits, bodies, soul, the arts as portals, destiny, stars, and humor. (We can't take the time to define these things here...and spend a good part of our training leading participants to experiences of these realities.)

3. Anthroposophic Psychology... Caring for the Human Soul By Roberta Nelson, Ph.D.

"We live in a time where psychological wellbeing is increasingly threatened by the prevailing materialistic world view of the soul. For decades, individuals discontented with this paradigm have sought for answers to their riddles by embracing Eastern spirituality. Yet, for over a century there has been a spiritual scientific framework for understanding the wisdom of the soul. The fact that it has remained largely unknown and little developed is one of the great oversights in the field of psychology. Rudolf Steiner's penetrating perspectives, given in a lecture cycle in 1910 entitled: The Wisdom of the Soul - Psychosophy, remain as pertinent today as they were then."

(William Bento, 1950-2015, Founder of Anthroposophic Psychology Seminars in USA).

The urgent call to build a true relationship to the sources of knowledge is nowhere more truly felt than in the search for a psychology of soul and spirit worthy of the dignity of the modern human being. Ancient writings give reference to the soul's intimate and authentic connections with universal spiritual principles illustrated in this quote from the Chhandogya Upanishads: "The spirit is below, above, to the west, to the east, to the south, and to the north. The spirit is, indeed, the whole world" (Joseph Campbell, (1986). Inner reaches of outer space. p. 18).

This photo was taken in September 2016, in a North American wilderness region where the Cree Native American Indians once lived in great numbers. It speaks to the experiences of Native Americans who knew the "Great Spirit" that revealed itself in four directions and in four elements: in land, in water, in the air, and in fire.

This photo was taken in September 2016, in a North American wilderness region where the Cree Native American Indians once lived in great numbers. It speaks to the experiences of Native Americans who knew the "Great Spirit" that revealed itself in four directions and in four elements: in land, in water, in the air, and in fire.

The North American indigenous people's understanding of the "Great Spirit" echoes ancient peoples of China who identified their leaders as "Son of the Sun" ruling over the universe, which was divided into four directions symbolized as the Azure Dragon of the East, White Tiger of the West, Black Tortoise of the North, and the Vermillion Bird of the South.

The relationship of the psyche, or soul, to the heights, depths, and the widths, acknowledged in ancient cultures in four elements and four directions, is rekindled anew in Anthroposophic Psychology seminars appropriate to our times. The seminars present a holistic view of human nature which includes the understanding that we are affected by changing cosmic and earthly aspects.

Recognizing that human nature is stimulated from two dimensions, cosmic and earthly, is not new. The ancient Emerald Tablet, displayed in Egypt in 330 BC, proclaimed a correspondence between the macrocosm (cosmic) and the microcosm (earthly): "That which is below is like that which is on high...." From the heights we are inspired by spiritual realities. From the depths and the widths, the soul is vulnerable to the forces of the four elements of nature: fire, air, water, and earth, hailed by our forebearers. Persons enrolled in the Anthroposophic Psychology training explore the relationship between the element of fire and personality disorders; the element of air and psychotic, trauma, and stressor related disorders; the element of water and depressive disorders; and the element of earth and substance related and addiction disorders.

Contemporary psychology is known as the study of the psyche or soul, which it elaborates as the examination of the human mind and its functions. From an anthroposophic orientation, the soul is more than the mind. Instead it is viewed as a key to life and the world. It consists of three dynamic multifaceted interrelating forces: thinking, feeling, and willing. Unique to anthroposophic psychology is its view of the psyche or soul as an intermediary open to cosmic influences known as the supersensible as well as forces of nature recognized as materialistic or sensory phenomenon, which can be measured and quantified. Like the rainbow placed between the sky and the earth, the soul mediates between the spiritual and bodily dimensions of our being.

Contemporary psychology is known as the study of the psyche or soul, which it elaborates as the examination of the human mind and its functions. From an anthroposophic orientation, the soul is more than the mind. Instead it is viewed as a key to life and the world. It consists of three dynamic multifaceted interrelating forces: thinking, feeling, and willing. Unique to anthroposophic psychology is its view of the psyche or soul as an intermediary open to cosmic influences known as the supersensible as well as forces of nature recognized as materialistic or sensory phenomenon, which can be measured and quantified. Like the rainbow placed between the sky and the earth, the soul mediates between the spiritual and bodily dimensions of our being.

We possess slumbering faculties that do not automatically kick-in. Awakening our dormant faculties requires knowledge and effort. If recognized and nurtured, they can uplift and inspire our psychological or soul makeup. Transforming our soul ─in other words, our thinking, feeling, and acting─ is contingent upon the realization and development of the scope of the “I” or “Ego.” (Not to be confused with the psychodynamic understanding of the ego.) We can learn, by mobilizing the inner light of attention, or the “I,” to observe, control, and then change our limiting, harmful thoughts, feelings, and actions. We possess fears. We are driven by all sorts of desires and compulsions. Anthroposophic psychology seminar content reworks the established understanding of these common difficulties and diagnoses while clarifying that we are other than our burdens. “I have anxiety but I am more than my anxiety!” “I have addictions but I am more than my addictions!” Overall, this schooling course responds to the claim and question: If we are not our burdens, who are we then?

"The experience we call the 'I-am' experience. It is the universal healing medicine. It is a feeling of identity with an ever-deepening being that wills itself. It provides certainty, creativity, and solidarity, and dissolves what comes from egotism. From it, the knowledge arises that nothing can happen to me: I am safe, completely independent of circumstances, opinions, successes or failures. I have found my spiritual roots."

(Georg Kuhlewind. The Light of the I. page 39).

Who we truly are ─the image of the human being─ is in danger of being lost to humanity because, in part, owing to our reductionistic view of human nature and development; because of our view that we are merely biological chemical beings whose nerve-sense system causes consciousness. Anthroposophic psychology is devoted to an education and application of a holistic orientation towards human nature and development. The anthroposophic image of human nature can enhance contemporary psychology since it incorporates a three-fold understanding of the soul, while accepting that the body and soul are informed by spiritual realities and principles, which are of a different class than our physical ones. The course honors natural scientific principles while giving equal value to life processes, soul dynamics, and spirit realities, such as the “I.”

The illuminating principles of anthroposophic psychology are enlivened and embodied thru experiential and artistic activities designed for the non-artist. Imaginative activities aid comprehension, application, self-discovery, and change. Woundedness is understood as an opportunity instead of a burden. Pathologies are considered initiation pathways, a hero or heroine’s journey towards what is good, beautiful, and true.

"Anthroposophy is a path of knowing, to guide the Spiritual in the human being to the Spiritual in the universe."

(Rudolf Steiner. Anthroposophical Leading Thoughts. page 13).

AAP Anthroposophic Psychology Seminar Themes: Anthroposophic psychology can help us understand the magnitude of who we are by intentionally and gently engaging our depths while embracing our heights. It recognizes that whether we are a clinician, a teacher, a farmer, a nurse or in a mental health or a service profession, whether we work in an office or outside, we are frequently “counseling” others: our clients, our patients, our co-workers, our friends, and our loved ones.

AAP Anthroposophic Psychology Seminar Themes: Anthroposophic psychology can help us understand the magnitude of who we are by intentionally and gently engaging our depths while embracing our heights. It recognizes that whether we are a clinician, a teacher, a farmer, a nurse or in a mental health or a service profession, whether we work in an office or outside, we are frequently “counseling” others: our clients, our patients, our co-workers, our friends, and our loved ones.

The constant in all of our encounters is the self. In the addiction profession there is a saying: “Wherever we go there we are!” We can’t escape ourselves, although we often attempt to do so through all sorts of distractions and amusements; through addictions; through denial; through blaming others; through immersing ourselves in our work or screen time, and so on. Nevertheless, despite our diversions, if we slow for an instant, or a crisis arises, or whatever it is that shakes us awake, we still have ourselves. “Wherever we go there we are!” Yet, how much do we know about this incessant factor? Have we participated in educations that delivered psycho-spiritual knowledge and training on the dynamics of the self?

The following is a partial list of themes that are explored by persons who participate in the AAP Anthroposophic Psychology seminars. For additional information refer to the three-year curriculum.

- An integrative, holistic approach to psychology and counseling

- Who we are and can become

- Recognition of the bodily nature of the human being as consisting of a physical body, a life body, and a desire body

- Recognition of a threefold soul nature which mediates between the bodily and spiritual components

- The sevenfold life processes including their corresponding fallen processes

- The twelve personality disorders, and the twelve virtues and vices

- The anatomy of the soul

- Seven processes designed to foster adult learning and change

- Relationality with self, with others, with nature, and with spiritual beings

- How self-sabotage obstructs self-actualization, development and relationships, while simultaneously offering opportunities for becoming and healing

- Exploration of the sacred and the primal wound

- How the soul unfolds through the tension between polarities

- Four levels of self: the pre-personal self, the personal or earthly self, the transpersonal or higher Self, and the universal Self

- Self-realization through awakening and strengthening the "I-organization"

- Heartfulness and other exercises that increase our ability to respond with compassion and empathy to self and others

- Pathology and personality disorders from a psycho-spiritual viewpoint which perceives patients and clients as Seekers.

"Spirit Soul Emerging:

Deeper aspects of soul life will be presented from an anthroposophic standpoint. By placing the human soul within an evolutionary context, it becomes self-evident that development of new faculties for seeing the spirit in matter is essential. Developing such faculties is at the heart of anthroposophic psychology."

(William Bento)

4. Introducing Anthroposophic Psychology in Relation to Mainstream Psychology by David Tresemer, President AAP

"Anthroposophy" was formulated as a philosophy in the early 1900s, exploring the wisdom (Sophia) of the possible-human-being (Anthropos). Anthroposophy was applied to many aspects of human affairs, including psychology. The tenets of an anthroposophic psychology (AP) are found in many places in the works of the Austrian philosopher Rudolf Steiner, especially in Steiner (1999). These tenets have been organized and developed further by Bento (2004) and by various authors in Tresemer (2015, 2016a, 2016b, 2017), including, in The Counselor...As If Soul and Spirit Matter, a section on reformulating contemporary clinical issues (addiction, depression, trauma, and personality disorders) both within mainstream psychology and from the point of view of anthroposophic psychology.

AP emphasizes a health (rather than illness) orientation, what has been called salutogenesis; all modern pathologies are seen as a continuum (or spectrum) that extends from healthy patterns to dysfunction. While embracing the exciting new scientific research from neurology and biochemistry (e.g., Siegel, 2015, as a flagship for presentation of these breakthroughs), AP notes the well-documented limits of these approaches (e.g., Whitaker and Cosgrove, 2015, and van der Kolk, 2015). AP also explores the very well designed studies (scientifically designed, and thus considered "evidence-based") for intrapsychic phenomena (e.g., Shedler, 2010, 2016) as well as extrapsychic- or field-phenomena (e.g., the carefully controlled studies in Radin, 2013, 2016, and Sheldrake, 2012, and other studies).

AP draws upon the main traditions of psychology, including the foundations of psychology (James, Freud, Jung, Maslow, Rogers, Assagioli, Bowlby, Winnicott, Gendlin) as well as the more recent "evidence-based" studies of various techniques in relation to many issues, ranging from pathology to improved learning techniques. We are guided by the work of Shedler (2010, 2016) on the research-confirmed efficacy of relational techniques for a wide range of issues. Anthroposophic psychology has contributed to, and draws from, advances in narrative therapy, transpersonal theory, person-centered therapy and its successor motivational interviewing, logotherapy, Jungian analytical theory and therapy, mindfulness, positive psychology, psychosynthesis theory and therapy, bibliotherapy, and others.

References

- Bento, W. (2004). Lifting the veil of mental illness: An approach to anthroposophical psychology. Great Barrington, MA: SteinerBooks.

- Radin, D. (2013). Supernormal: Science, yoga, and the evidence for extraordinary psychic abilities. New York: Crown/Deepak Chopra.

- Radin, D. (2016). Selected peer-reviewed psi research publications. Retrieved from www.DeanRadin.com/evidence/evidence.htm.

- Shedler, J. (2010). The efficacy of psychodynamic psychotherapy. American Psychologist, 65(2), 98-109.

- Shedler, J. (2016). JonathanShedler.com, many citations of research studies demonstrating the effectiveness of relational psychotherapy and relational counseling equal or superior to CBT (cognitive-behavioral therapy).

- Sheldrake, R. (2012). The presence of the past: Morphic resonance and the memory of nature (4th ed.). New York: Park Street Press.

- Siegel, D. (2015). The developing mind (2nd ed.). New York: Guilford.

- Steiner, R. (1999). A psychology of body, soul, & spirit: Anthroposophy, psychosophy, & pneumatosophy (original works 1909-11, edited by Robert Sardello). Hudson, NY: Anthroposophic Press.

- Tresemer, D. (Ed.). (2015). The counselor ... As if soul and spirit matter. Great Barrington, NY: SteinerBooks.

- Tresemer, D. (2016a). Anthroposophic psychology. In Hagedorn, W. B., Cashwell, C. S., Lenes, E., Foster, K. J., Brennan, C., Tresemer, D., Vossenkemper, T., Kondili, E., Heard, N., & Pennock, E. On common ground: Counselors of varied spiritual and religious backgrounds engage in case discussion. Program presented at the national conference of the American Counseling Association, Montreal, QC (March).

- Tresemer, D. (Ed.). (2016b). Slow counseling. Phoenixville, PA: Lilipoh Publishing.

- Tresemer, D. (2017). Love and hate as soul phenomena. Self & Society (in press).

- Van der Kolk, B. (2015). The body keeps the score. New York: Penguin.

- Whitaker, R., and Cosgrove, L. (2015). Psychiatry under the influence. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Many other reference works within the discipline of anthroposophy, as well as within mainstream psychology, are referred to in the reference list at the end of Tresemer (2015).

Example of a Module on Addiction

As an example, in our presentation on addiction, we introduce the topic as follows:

Clinical Issues: Addiction

Course description:

Addictive patterns can be seen in relation to substance (food, drugs, ...) and processes (gambling, internet, excessive exercise, ...). We will address the phenomena of addiction, as well as the dynamics of addiction, and learn some approaches to dealing with addictive patterns, examining mainstream counseling psychology as well as finding what anthroposophy can contribute. The tetrad model from anthroposophic psychology will be applied as a helpful way to differentiate addictive processes from other pathological patterns.

Learning objectives:

Participant will be better able to

- Identify six or more key characteristics of addictive processes.

- Identify the full range of addictive patterns, including substance and process addictions, and their less obvious pre-addictive markers.

- Identify these characteristics working within his/her own behavioral and emotional patterns.

- Identify the main argument between a completely physical understanding (brain-reward, biochemical, genetic) and other influences within the AP (anthroposophic psychology) tetrad of physical, vitality (life-body), mentation (within which the triad of cognition-affection-volition), and sense of "I" (both the less developed ego and the higher sense of Self).

- Relate addiction processes to the underlying dynamics of sympathy-vs.-antipathy.

- Name foundations for the approach of a counselor to any addiction pattern.

- Identify the main resources in the literature in the field of addiction.

Essential introduction:

- Nelson, Roberta, and Bento, William. (2015). Addiction. In D. Tresemer (Ed.). The counselor ... As if soul and spirit matter (chapter 9, pp. 221-253). Great Barrington, MA: SteinerBooks.

Mainstream psychology:

- Dailey, S.F., Gill, C.S., Karl, S.L., and Minton, C. A. B. (2014). DSM-5: Learning companion for counselors. Alexandria, VA: American Counseling Association. A very helpful overview of the DSM-5 criteria with relevant studies is given in chapter 9, "Substance-related and addictive disorders," pages 149-163.

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Substance-related and addictive disorders. In Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.; known as DSM-5; pp. 481-589). Washington, DC: Author. This is the basic reference, though it cites only one process addiction (gambling), a shortcoming commented on in R. Smith's Treatment Strategies (below).

- Love, T., et al. (2015). Neuroscience of internet pornography addiction: A review and update. Behav Sci (Basel), 5(3), 388-433. (Available at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4600144/). This is a very thorough overview of internet addictive patterns of all kinds, and gives a framework for the newer addictions not covered in the DSM-5.

- Resource: American Society of Addiction Medicine, asam.org.

- Resource: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, samhsa.gov.

From the point of view of anthroposophic psychology (in addition to the essential introduction):

- Treichler, R. (1989). Soulways: Development, crises, and illnesses of the soul. Stroud, UK: Hawthorn Press. Pages 64-69, though brief, are extremely helpful for a broader understanding of addiction issues, in the context of the author's wide clinical experience.

- Tresemer, D. (Ed.). (2015). The counselor... As if soul and spirit matter. Great Barrington, MA: SteinerBooks. Other pages will be cited, including the introduction to the section "Reformulating Contemporary Clinical Issues," (pp. 155-162).

- Dunselman, R. (1993). In place of the self: How drugs work. Stroud, UK: Hawthorn Press. This gives a very readable account of a broader picture of various substance abuses, and their effects on the personality organization (and disorganization) specific to each class of substance.

Sample assessment source:

- We will survey a few of the assessment tools used for addictive processes, and discuss their benefits and drawbacks.

- Babor, T. F., Higgins-Biddle, J. C., Saunders, J. B., and Monteiro, M. G. (n.d.) AUDIT: The alcohol use disorders identification test: Guidelines for use in primary care (2nd ed.). World Health Organization. The self-report test is on page 31. Each participant will take that test. (And see Saunders, J.B., Aasland, O.G., Babor, T.F., et al. (1993). Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO Collaborative Project on Early Detection of Persons with Harmful Alcohol Consumption-II. Addiction. Jun, 88(6):791-804.)

Therapeutic approaches:

- Smith, R. L. (Ed.). (2015). Treatment strategies for substance and process addictions. Alexandria, VA: American Counseling Association. We will work with chapters 1 (pp. 1-32) and 14 (the last, pp. 313-328) by the editor, Robert Smith, a past president of ACA. We will touch on all of the addictions that are presented in this book, especially with Todd Lewis's chapter 2 on "Alcohol Addiction" (pp. 33-56) and Joshua Watson's chapter 13 on "Internet Addiction" (pp. 293-312).

- Simpson, L. R. (2011). "Dialectical Behavior Theory," chapter 10 in D. Capuzzi and D. R. Gross (Eds.). Counseling and psychotherapy: Theories and interventions (5th ed.; pp. 215-236). Alexandria, VA: American Counseling Association. We will examine the particular techniques of DBT in relation to addictive patterns. David Capuzzi, a past president of ACA, has assembled a wide variety of techniques in relation to the common case of Maria.

- McWilliams, N. (2011). Psychoanalytic diagnosis: Understanding personality structure in the clinical process (2nd ed.). New York: Guilford. As we follow this brilliant book in relation to a wide range of disorders, we shall note the important brief discussion concerning addiction on page 174.

- Gladding, S. T. (2016). The creative arts in counseling (5th ed.). Alexandria, VA: American Counseling Association. This gives the research on various methods used with addictions, especially drama, literature, music, and poetry.

Case presentation:

- A case will be presented, and worked on by the group in relation to the various approaches to diagnosis and therapy.

5. What is AAP by Christine Huston, AAP Associate

The Association for Anthroposophic Psychology (AAP) carries an ambitious shorthand mission statement: Re-membering Psychology through Relational AnthropoSophia.

Re-membering: putting back together a holistic view of the human being, Body, Soul and Spirit – anything and everything affecting one of these three affects them all.

Relational: In our interactions with others we receive feedback about ourselves. What do I need to change? How can we support the Self and others in our mutual development?

AnthropoSophia: Anthropos, the “becoming” human being, and Sophia, the eternal feminine element bestowing wisdom.

Mainstream psychology tends to a materialistic model of the inner life, as the working of genes and chemicals, and often responds with medications. “Soul,” with her forces of Thinking, Feeling, and Willing, is completely forgotten, as “Mind,” which can be manipulated into taking a more comfortable view of life, has become the popular imagination of inner life. If that manipulation doesn’t work, then drugs are administered to make life more comfortable.

But is comfort in life a worthy goal? Is that the best use of our time on Earth? How can discomfort (even suffering) serve us? When life is good and nothing pinches, there is no impetus to change. But, we’ve come to Earth, haven’t we, in order to have experiences, to learn, to grow – that is, to change?

The Association for Anthroposophic Psychology (AAP) offers richly diverse and intensive programs to support individuals in exploring the human soul, in a personal process of “becoming,” through:

- studying both theory and knowledge of the human psyche developed over millennia

- exploring our own psyche, our actions and reactions and their origins

- learning the skills of self-observation and inner development work

- enhancing our ability to be in fruitful relationship to others

- asking the existential questions that make our individual lives a profound journey

NOTE: there is also a specialized program in psychotherapy offered for licensed professionals.

AAP is a member of the Anthroposophic Health Association (in North America) as well as the International Federation of Anthroposophic Psychotherapy Associations. Through the latter, AAP is recognized by the Medical Section of the School of Spiritual Science at the Goetheanum in Dornach, Switzerland.

6. About AAP by Dr. James Dyson, AAP Faculty Member

The Association for Anthroposophic Psychology (AAP) recognises that the human being encompasses a totality of experience in Body, Soul and Spirit. Looking beyond these initially abstract terms, Anthroposophic Psychology seeks to explore the reality of each of these three aspects of existence. It offers a unique insight into their combined development, integration and embodiment, as well as an understanding of how their more-or-less optimal expression manifests in our so-called “psychological make-up”, with our individualised capacities for volition, for feeling or emotion, and for thought. This is viewed in the context of a wider process of becoming, one which may be seen to span a sequence of experience that encompasses repeated earthly lives. This perspective allows factors such as destiny, karma, and ultimately meaning, to be embraced and worked with within the relational framework a therapeutic encounter.

The Association for Anthroposophic Psychology (AAP) offers richly diverse and intensive programs to support individuals on this path of human understanding. Specific support programs, seminars, and courses are held regularly for therapists, practitioners, supervisors, and also for general interest.

AAP is a member of the Anthroposophic Health Association (in North America) as well as the International Federation of Anthroposophic Psychotherapy Associations. Through the latter, AAP is recognized by the Medical Section of the School of Spiritual Science at the Goetheanum in Dornach, Switzerland.